Brian McDowell, a National Board certified teacher, is a STEM and Project Lead The Way teacher for Mason County Middle School in Maysville, Kentucky. He has received the Kentucky Science Teachers Association’s Middle School Teacher of the Year Award and the National Science Teachers Association’s Inquiry Based Teaching Award, was a Presidential Award Finalist, and has been awarded more than $70,000 in grants over the past eight years.

In search of a sustainable response to the lack of engineers in my eastern Kentucky community, my school district has invested resources into the creation of a K-12 STEM pipeline using Project Lead The Way. My role was to develop the middle school program, and it became obvious quickly that the program would be stronger with the help of local industry.

But, what does that relationship look like? How should I start?

As I networked with other STEM teachers, the most common suggestion was to bring in guest speakers. From past experience, I knew this wasn’t always a great idea. Although guest speakers are incredibly knowledgeable, they are not professional teachers and may overwhelm the students with technical jargon or bore them with unimportant details. I’ve watched my middle school students’ facial expressions change from excited to distressed minutes into a presentation. I knew there had to be a better way.

After a visit to a local manufacturer, Stober Drives Inc., my belief was confirmed. What my students needed were engineers as coaches, not lecturers. My challenge, then, was to create an experience that allowed this collaboration to happen. After a few discussions with Adam Mellenkamp, a mechanical engineer at Stober, we had our plan. The engineer Skyped into our classroom and described a problem his company couldn’t figure out. He asked the students to design a way to attach tools to the gear boxes Stober created, and my students accepted the challenge.

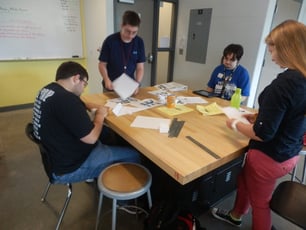

During the next few classes, we brainstormed and tested possible solutions. Students’ measurement skills grew as they realized their solutions had to match the measurements given in the blueprint. As students built prototypes, they explored advantages of different materials' properties (foam, wood, plastic). My middle school students liked to test prototypes but had room for improvement when it came to using what they learned to re-design. Having the engineer advise our students through the re-design process showed them the recursive cycle of learning from, and responding to, evidence.

As I walked through the school, I caught students discussing possibilities during passing periods. Parents asked about the project and were amazed by the connections to our own community. As a capstone experience, our students presented their solutions to the engineer, practically overflowing with the confidence they’d gained.

Most importantly, this collaboration was not difficult. I facilitated the experience as I had done for my own lessons. The engineer advised us as he advised his own employees. I asked questions to prompt organization, testing, and reflection, while the engineer supplied the experience to make the solutions possible.

The positive response from community partners and students prompted me to build on our success: Could we make celebrities out of engineers?

Traditionally, STEM courses have students do web searches to find multiple examples of careers within a given field. I took that idea and made it more local by creating engineer "baseball cards." I started with parents of students who worked as engineers. They sent me selfies taken at work, and I added some basic facts. After exploring the engineering baseball cards, I challenged students to find other engineers in our community, introduce themselves, ask them their questions about their careers, and take a selfie to prove it happened. If we want our local engineers to be role models, why not treat them like sports stars?

As parents and community members began to talk about our program, other partnerships were added. Another manufacturing plant, Mitsubishi Electric Automotive, sponsored the bus transportation for students going to Engineering Day at the University of Kentucky. Many students who attended would have been unable to without the generosity of Mitsubishi.

We partnered again with Stober to create a submission for a regional video contest entitled “What’s Cool about Manufacturing?” Students planned, shot, and edited the movie after a tour of the plant. The final version was award winning and will be used as a recruiting tool for Stober for years to come.

There can be financial advantages, also. Teachers are amazing at creating incredible classroom experiences with few resources. For many industry partners, contributing funds to education is not just doable, but part of their annual giving plan. As partnerships develop, industries are more willing to invest in your program because they understand and appreciate your school’s track record. My school has added a 3D printer, multiple robots, and numerous inquiry areas along our nature trail because of community partnerships.

Ultimately, my experiences have changed my teaching practice. For example, as I began a design project about collisions for my sixth grade students, it seemed natural to reach out to one of my parents who is an engineer at Ford Motor Company.

For more information, please explore http://teachinginmargins.weebly.com/ or contact me.

PLTW’s blog is intended to serve as a forum for ideas and perspectives from across our network. The opinions expressed are those of each guest author.